Tomorrow’s tech policy conversations today

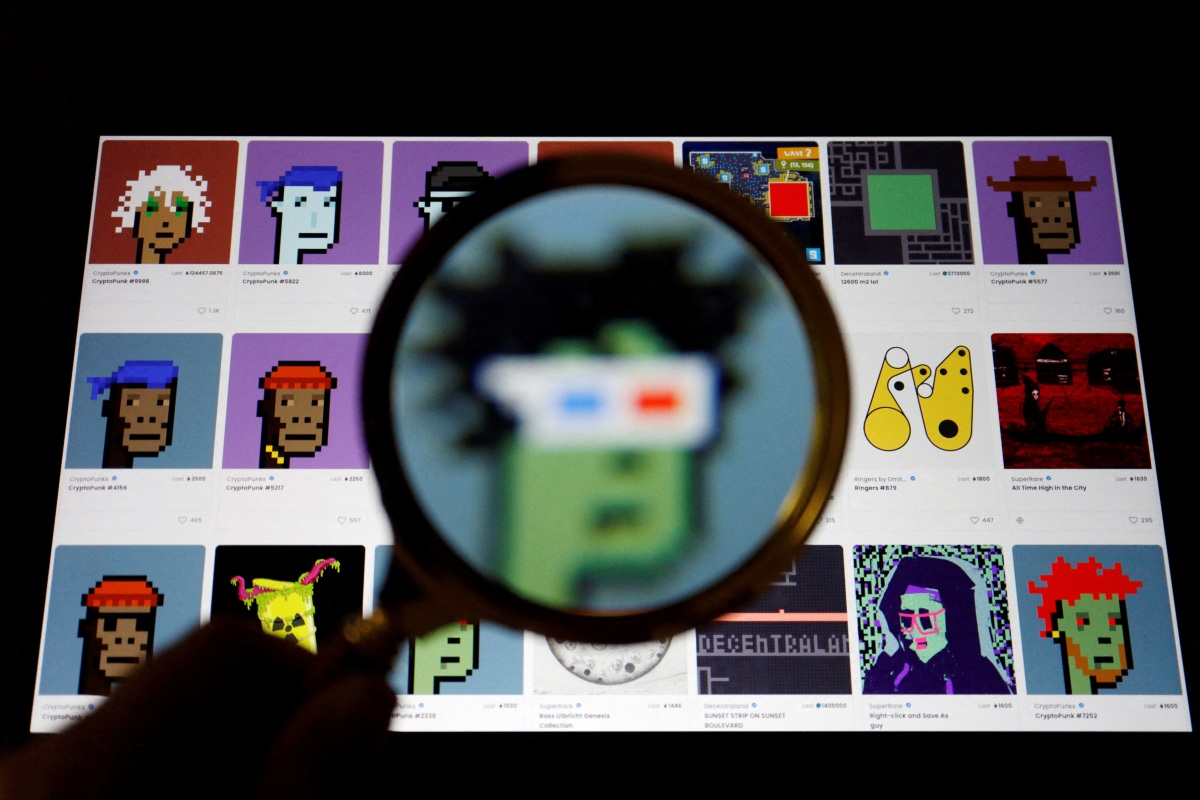

At the end of March, hackers pulled off an audacious heist, stealing $625 million from the blockchain that powers the popular video game Axie Infinity. While not well-known in the United States, Axie Infinity is the most prominent and popular example of a new model for gaming, in which users get paid to play. This innovative play-to-earn business model gives players a financial incentive to stick with the game for the promise of regular income. It does this by minting non-fungible tokens, or NFTs, to represent the game characters known as “axies.” Inspired by Pokemon, the axies are digital creatures, each represented by an NFT that players can use for battle, cultivation, or trade. When hackers believed by the U.S. government to be linked to North Korea raided Axie Infinity in March, they wiped out many players’ earnings.

Axie Infinity raises important questions about the nature of gaming, the nature of play, and the relationship of play to labor. To participate in the game, players must purchase three axies, whose prices can vary widely. In the last year, it has cost upwards of $1,100 just to start playing the game. Such a steep entry cost would be a barrier for any other gaming platform, but the promise of Axie Infinity’s design is how NFTs have created a unique economy in which players earn surprising amounts of income. The “play-to-earn” model, as it’s often called, has the potential to upend the economy of gaming. Axie Infinity takes a 17% cut from every transaction in the game, generating revenues of $700 million in 2021 (though those numbers have since sharply dropped alongside the collapse in cryptocurrency prices). Big tech funders have noticed. A recent $152 million capital injection into Sky Mavis, the developer behind Axie Infinity, valued the company at $3 billion.

NFTs ostensibly create a chain of unique ownership for digital assets, but by manipulating consumers and companies into approving trades they don’t understand, hackers can infiltrate this chain and redirect the money to themselves, allowing half a billion dollars vanish from the wallets of unsuspecting players. The Axie hack is indicative of the risks built into the evolving nature of video game marketplaces and demonstrates the need for regulators to implement better monitoring and consumer protection schemes.

The lines between play and labor in video games have long been blurring. For the last 19 years, players of Eve Online—a massively multiplayer online game, or MMO—have been able to mine resources and sell them at a marketplace, making the game a pioneer in integrating monetary transactions that make it difficult to distinguish between play and labor in video games. Eve Online places players at the helm of various spaceships, which can be optimized for either mining in-game resources or building specialized combat vessels. The game has a unique structure: Whereas other MMOs allow players to “farm” powerful items through combat and quests, Eve only allows farming of raw resources, known as “mining” in the game. Once enough materials are mined, they can be sold at a marketplace for real world currency, like U.S. dollars, and the raw materials can be crafted into items and ships. This makes the game reliant on player labor to generate new items in the game and to keep the economy flowing.

In many online games, players engage in uncompensated labor to advance through the game world. But the “grind” of doing repetitive or time-consuming tasks results in a better game character or more items, not real-world money. Grinding is often a way to draw out the time it takes to complete a game, and it can help players enter a meditative state of mind where they aren’t actively strategizing how to advance. But it would be a mistake to say that grinding is popular. Many gamers resent too much of it in a game and, especially when tied to a hypermonetized business model, liken it to doing a job, rather than playing. Researchers have identified this dynamic as “playbour,” in which players engage in ordinary play that also generates income, whether virtual or real. In Eve Online, the players who focus on mining are known as “industrialists,” and their position as the foundation of the in-game economy is one way to understand how labor and play are growing less distinct. Since there is an in-game currency convertible to dollars, and even an on-staff economist to oversee the market, it is not clear where the line between player and worker exists, if at all.

Despite in-game markets serving a key role in the game, Eve Online players have fiercely resisted attempts by its developer, CCP, to incorporate NFTs into the game and change its monetization systems. CCP’s attempts at reforms have sparked a massive backlash, leading to protest, ritual destruction of in-game currency, and thousands of angry messages to the developer. But was this just a player backlash or was it more like a labor strike? It may very well have been both, and the ambiguity of whether players who earn money from playing a game count as workers, contractors, or nothing at all, has created an unregulated space many game makers are eager to move into.

Axie Infinity is a prominent example of how the business models behind video games is changing. Most online games tend to measure their success based on player engagement, since the more time someone spends in the game world the more likely they are to purchase in-game items. But what if a company could add a financial incentive to that time? A player might spend more time playing the game, and thus engage more with jts revenue generating functions. NFT-based gaming promises to make the labor of fun into compensated labor. This is the play-to-earn model, where players receive financial rewards for playing a game, most commonly through the appreciating value of cryptocurrency and NFTs. Thus, the more players play, the more money they earn. In Axie Infinity, the basic cycle of game play works like this: Completing levels creates stronger axies to win matches, which provides users with a token that allows axies to “breed” and thus create new axies to be sold or used for play.

Video game makers are rushing to adopt this technology before regulations restrict potential income streams. Developers like CCP Games (Crowd Control Productions, the Reykjavik-based developer of EVE Online) want to incorporate NFTs into their business models to drive ongoing, passive revenue. The crypto marketplace FTX is trying to launch its own line of game oriented NFTs. Large companies like Ubisoft are creating their own, proprietary line of NFTs to be used in their game properties, though, like CCP, has faced intense opposition from gamers. Publishing giant EA called NFT games “the future of the industry” in a recent earnings call, though the company quickly reversed course after yet another player backlash.

This push to incorporate NFTs into video games is an evolution of the live services business model, which is a game that features continuing updates and items purchased in small transactions. Traditionally, video games were released as a discrete item (like a cartridge or CD). As internet connectivity improved, developers could fix bugs or expand content via downloads. Game publishers soon learned that creating an ongoing stream of paid game content could create much more revenue from a development cycle than a single product shipment, which coalesced into the idea of Games as a Service, or GaaS. The potential profit of this model is enormous. In 2019, for example, the live service FIFA Ultimate Team generated over $1.6 billion just from these small transactions. For the publishing giant EA, live services now generate upwards of 70% of company revenue, a sharp change from how game publishers used to generate income. But as the gaming journalist Stephen Totilo explains, live service games require not only the tens of millions in upfront development costs but many more “to keep content flowing.”

Incorporating NFTs into this business model has the potential to create new opportunities for game makers to grow their revenue. NFTs can be sold to players the same way other downloadable content can be: as a product sold from a store, where the initial sale includes a profit for the developer. But these tokens can be coded with what’s known as a “smart contract,” a piece of code built into the NFT that sends a royalty payment to the originator of the token—in this case, the game company. Such a model allows game makers to re-monetize items again and again, using the prospect of future player-to-player sales to generate an ongoing revenue stream.

Such a model bears a superficial resemblance to already-existing markets for game items. World of Warcraft built a famously rich ecosystem for players to resell in-game items in the early 2000s. And Steam, the largest PC game marketplace operating today, runs a limited market for items, modifications, and other forms of game content. For a game like Axie Infinity, by contrast, the sale of axies or other in-game items can take place anywhere, allowing for more player-to-player interaction that the game’s publisher does not have to monitor. In theory, this should unleash player-to-player commerce and drive up revenue through royalties built into the NFT smart contract. This approach to in-game items is a twist on the microtransaction model. Many gamers complain that games that embrace microtransactions—especially from the large publishers like EA and Ubisoft—end up exploiting players through opaque designs that hide how much money is spent (I have called this dynamic “hypermonetization” to underscore that it is an extreme practice). The incorporation of NFTs into games only further conditions participation on using a complex, difficult-to-understand financial instrument.

NFT-based gaming promises to make the labor of fun into compensated labor, but the tension between play and labor may never go away, as companies experiment with play-to-earn models and run up against player backlash. When Valve, the game publisher that owns Steam, tried to release a card game that functions almost exactly like an NFT game in 2019, it failed spectacularly. Blizzard tried to launch a marketplace based on game items when it released Diablo 3. The Real Money Auction House (RMAH) allowed players to auction items from the game but undermined a key element of the game: the need to play it. Instead, some players would simply buy and sell items at RMAH like commodity speculators, driving the price of some items sky high. It sucked the fun out of the game, and after a year in operation, Blizzard pulled the plug.

As video game publishers rush to incorporate NFTs into games, players are being exposed to ever greater financial risk. Many proponents of NFTs focus on the supposedly decentralized nature of the assets: The ledger that determines ownership is distributed, not centralized. But NFTs are not really decentralized—they rely on central marketplaces to aggregate NFT listings and facilitate sales, charging a percentage in transaction fees to support their operations (again, much like Axie Infinity). These marketplaces have security weaknesses, especially when they are not regulated by know-your-customer laws and similar protections built into securities trading. The contracts they hold are irreversible due to the distributed nature of the blockchain, which makes losses unrecoverable when theft occurs. The Securities and Exchange Commission has begun identifying places where NFTs are legally considered securities, which could subject NFT-based games to invasive scrutiny by regulators. But it could also impose onerous compliance requirements on players as well since they would have to treat their in-game items as financial instruments that must be reported to central agencies for taxation.

The incorporation of NFTs into video games also exposes players to the boom-and-bust cycles of cryprocurrencies. The industry is in the midst of an enormous bust, as a growing wave of companies restrict or outright ban withdrawals from their systems. Such a crackdown on transactions essentially traps customer money, denying the liquidity needed to make the broader market function. NFT games are not immune to this cycle: Before the hack, Axie Infinity players in the Philippines (Axie’s largest market), were so successful at making money trading NFTs during the economic disruption caused by the COVID-19 pandemic that some earned several times more than the minimum wage without having to pay taxes. It was one reason why the buy-in cost for the game became so expensive. In response, Sky Mavis tried to stabilize the market for Axie Infinity NFTs by tweaking valuations in the game economy, adjusting the value of the SLP tokens that allow axies to breed. But that tweak wiped out many players’ income even before the latest valuation losses for the cryptocurrencies that back up the game’s NFTs. What this and the current liquidity crisis have shown is that companies that rely on crypo will act much like a central bank does for a country, arbitrarily changing the “cost” of trading an NFT or coin in a way they hope will stabilize prices. But, just as when central banks readjust currencies irresponsibly, Sky Mavis’ intervention ended up destroying the appeal of the game in its core market (and, not coincidentally, mirroring the central complaint many blockchain promoters have with traditional fiat currencies: central, arbitrary control).

Games that incorporate NFTs borrow the computational complexity of cryptocurrencies and the ledger features of the blockchain to create unique assets that in theory should consistently appreciate in value, but this requires constant player growth to ensure payouts. This need to maintain growth creates a perverse incentive to prioritize new player acquisition instead of good game experiences. It functions like a pyramid scheme: The assets only grow in value if more players enter the marketplace, or if existing players purchase more. This presents players with risks they may not fully understand.

This is the central dilemma of NFT-based gaming. The victims who lost money in the Axie hack have no recourse—Sky Mavis also lost millions of dollars—and no insurance to guarantee the losses can be reversed. The way in which Axie Infinity payouts are tied to the value of an NFT is certainly novel but, as Sky Mavis’ attempt to reduce market volatility shows, even without a massive cryptocurrency crash players will be vulnerable to unpredictable prices should too many players or quit the game.

Perhaps in response to these risks, some video game makers are putting their own restrictions on the ways in which games can incorporate cryptocurrencies. Steam, the largest digital storefront for PC games, recently banned all games based on cryptocurrencies, placing a huge barrier to wider adoption of the technology in gaming. The co-founder of Valve, the company behind Steam, cited the high volume of fraud and scams being perpetrated through crypto assets like NFTs as motivating the ban. In contrast, Epic, the publisher of Fortnite, has said it is open to crypto and NFTs in its game stores, but only if they strictly adhere to reporting and tax laws.

While NFT games present risks to users, they also suffer from a lack of transparency about how security and valuation work. By blurring the line between player and worker, NFT games pose difficult questions about the shape of an appropriate regulatory response.

First, regulators at the Federal Trade Commission, the Commodity Futures Trading Commission, and the Securities and Exchange Commission need to take this technology seriously and identify the aspects of the technology that pose the greatest risk for consumer harms. Those weak points are continuously targeted by malignant actors for theft and fraud, and while traditional financial organizations must meet strict security and privacy standards, the purveyors of NFTs so far do not. Adopting a consumer-first mindset narrows this challenge to end results, rather than getting lost in the weeds of specific types of technology. Ultimately, the appeal of NFT games is the income they generate for both company and player, but that income should not take place outside the reach of systems of accountability or consumer protections. The recent crash in NFT and blockchain markets—losing investors millions of dollars without recourse—shows how an unregulated market can impose serious losses on consumers.

The difficulty faced by other games in incorporating in-game markets illustrates the scale of the challenge. EVE Online has struggled for over a decade to manage its in-game economy such that its players don’t run afoul of real-world laws about asset collection and taxation. They even keep an economist on staff to help manage a burgeoning market where spaceships can be worth thousands of dollars while limiting illicit activity. Doing so requires a level of monitoring and regulation that is anathema to the ethos of NFTs and crypto, but it does provide a means for law and financial enforcement to track transactions and ensure laws are being followed—even, potentially, labor laws.

The recent U.S. infrastructure bill classified NFTs as securities, which requires them to be reported to the government and taxed when they exceed $10,000 in trade value. In the EU, multiple countries are starting to tax cryptocurrency transactions and have imposed know-your-customer rules on crypto exchanges. These regulations will probably make NFTs “safer” for an average consumer to engage with, but they cut against the appeal and design of the technology and might strangle it before people can figure out socially constructive uses for it. Balancing the need to let new innovations flourish while limiting harm is an unending challenge for regulators, but they need to take NFT gaming, and the changes to game economies, seriously. This means devoting resources to understanding the myriad ways NFTs and cryptocurrencies can change the nature and behavior of digital marketplaces.

It remains to be seen whether NFT gaming really does become the future of gaming, or whether it is just another hypermonetized fad. As the novelty fades, it is just as likely that players will not tolerate the uncertainty and risks of NFT games. As an industry, video games are known for eagerly embracing new technology in the hopes that it will make a game better. While the play-to-earn model is promising as a revenue stream, it is unclear how necessary NFTs are to enhance the way we play games, especially given their rather significant downsides. You can still make a play-to-earn game without NFTs, it just won’t be as eye-catching.

Joshua Foust is a PhD student studying strategic communication at the University of Colorado Boulder’s College of Media, Communication, and Information. His website is joshuafoust.com.

Sign up for updates from TechStream