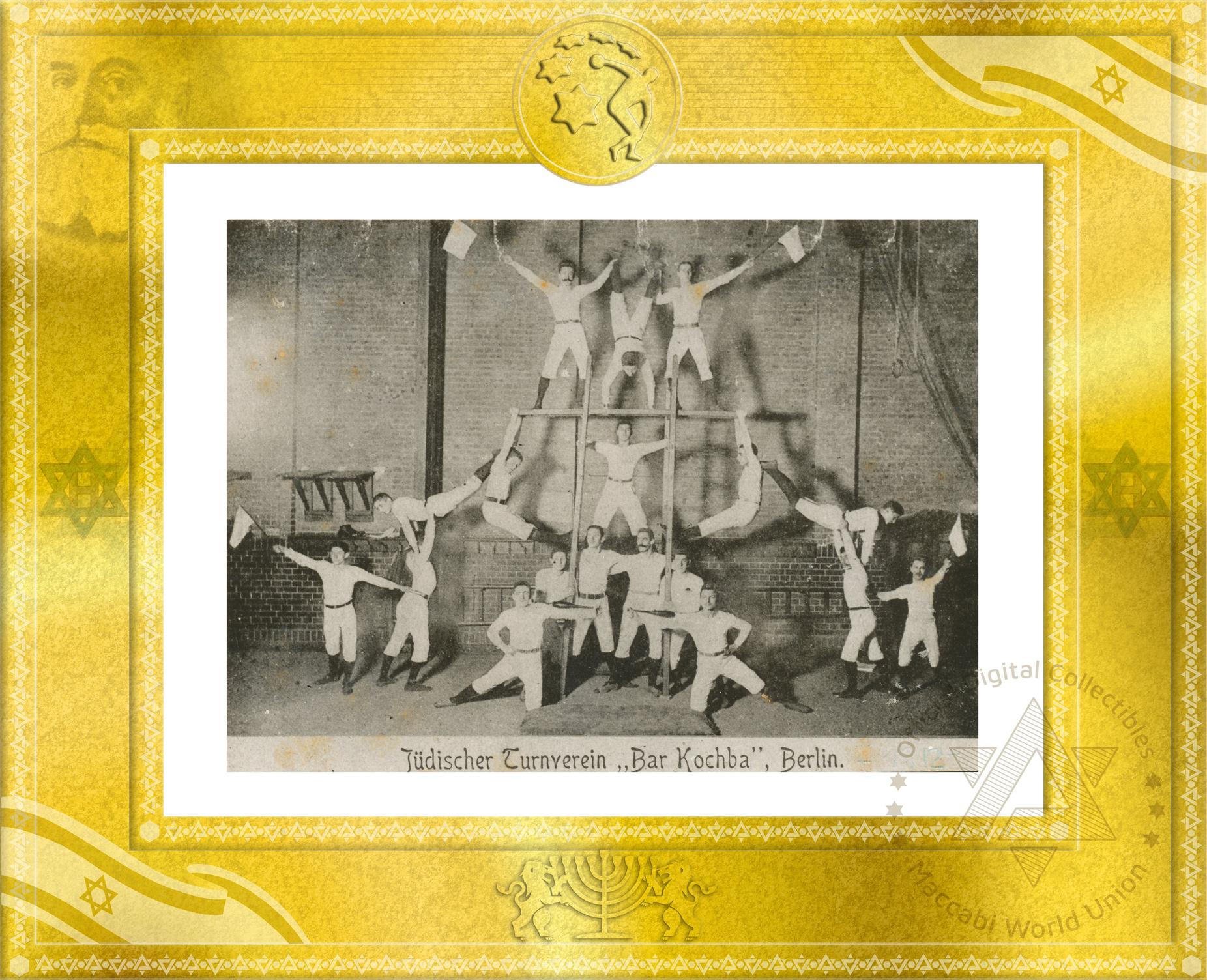

A “Project Max” NFT featuring a photograph of athletes from Bar Kochba Berlin, a first-of-its-kind … [+]

On a recent morning, Eran Reshef was touring an archive that will go on display at the soon-to-open Maccabi Museum on the outskirts of Tel Aviv. As he moved through the hundreds of medals, trophies, badges, flags, pictures, films, and memoirs from more than a century of sports competition, the Israeli entrepreneur kept thinking about how to move the past and present into the future. Inspired by his observation of the artifacts and wanting to find ways for technology to create connections between younger generations of people on social networks and in the metaverse, “Project Max” was born.

Project Max is an initiative that makes use of nonfungible tokens as a way to reach the public. The NFTs are officially-licensed digital memorabilia generated from Maccabi’s physical archives. But they do more than serve as the latest attempt by an established organization to grab on to the recent popularity of NFTs among collectors, investors, and speculators. They aim, instead, at bringing people closer together through meaningful messages about sport and society.

The project is a global awareness effort focused on promoting inspiring stories that connect with people through social media and the metaverse. It uses Maccabi’s trove of sports memorabilia as the basis for NFTs that elevate the message.

Maccabi is recognizable to many sports fans by association with major professional league teams in Israel that compete on international stages. Teams bearing the name regularly play in men’s football UEFA Champions League competitions and men’s basketball squads have won EuroLeague championships. And, for the past ninety years, the name has been known by way of male and female athletes participating in the quadrennial Maccabiah Games; the twenty-first edition of the Games took place this past month, with about 10,000 athletes from more than 60 nations competing in 3,000 events across 42 sports at venues in 18 cities around Israel.

Maccabi organizations have been playing an important role in their communities around the world since the late 19th Century. The movement has its roots in a call by the Hungarian-French physician and author Max Nordau for athletic, physical, and spiritual discipline that could revive a nation of the Jewish people. Today, the network of 450,000 members across 450 clubs in 80 countries organized under the Maccabi World Union. Over the past several years, however, there is a realization among its leadership that younger people are increasingly disengaging and distancing themselves from their heritage and identity. At the same time, antisemitism and other forms of hatred and intolerance are raging, especially online.

Rising levels of disengagement among people in a community and rising levels of online hate speech are often treated as separate challenges. But Reshef, the serial entrepreneur, sees them as interconnected. So, too, does Maccabi World Union executive Amir Gissin. Discussing that point following Reshef”s visit to the Maccabi Museum gave them a sense of tackling things from a new perspective. As Reshef explained to me, that sensibility, along with inspiration from Nordau’s name and vision, led to the development of Project Max and its NFTs.

One of the NFTs, for example, draws on a photo of athletes traveling to the first Maccabiah Games in 1932 as an opening to tell the story about a trip that ended up saving many of their lives because of what it did in leading them to escape the Nazi threat growing across Europe. A trophy from Maccabi clubs such as HaKoach Vienna, a winner of Austria’s national football championship in the 1920s, is a way-in to sharing stories ranging from the pre-war football and coffee house culture to the club’s wrestling team acting as security guards for teams in other sports to players emigrating and forming major teams outside of Europe to the liquidation of the club by the Nazis and the deaths of many members during the Holocaust. A lapel pin or a medal from clubs such as Bar Kochba Berlin, HaGibbor Prague, Maccabi Warsaw, Maccabi Bulgaria, or Maccabi Syria & Lebanon offer entry to stories about growth and change in those communities over time.

Even so, the NFTs might lean more toward novelty than utility were it not for the technology that Reshef had in mind while he was touring the Maccabi archives.

“Project Max” NFT featuring a photo of Austrian athletes on a train bound for the first Maccabiah … [+]

Reshef, along with veteran startup entrepreneurs Roni Reshef and Asher Polani, is a co-founder Israel-based startup Sighteer. The company, a pioneer in social-marketing, has developed an artificial intelligence platform that can reach specific audiences with related messaging at scale. The way that Reshef figured it, he said, was that Sighteer technology could be used to build the bridges that get Maccabi stories to the right audiences on social media and in the metaverse.

The Sighteer AI doesn’t get involved in public relations, media messaging, or marketing. What it does, as Polani explained, is “discover the identities and relationships that shape a community” and then assist in increasing the community’s global impact. With the Sighteer AI, an NFT is much more than a tradeable token—it is a key to how to run an efficient and effective community in the Web 3.0 world.

This is why Project Max, by design, weaves together three pillars that reflect and refract the power of sport in society. One is the values inherent to sports—winning and losing, competition, determination, persistence, individual and team work, and so on. Another is the role that sports and its values play as a driver of social movements. A third is the community of people from across generations and places throughout the world who gather around sports.

In that way, Project Max is an example of something more than minting and selling digital versions of historic artifacts housed in museum display cases. And it is about something more than the latest example of an organization using NFTs as a way to engage the public. Rather, it goes to show a new way of thinking about using the power of sport to attract people to more closely identify with their communities.