By Matthew Bultman

When federal prosecutors accused an ex-OpenSea employee of insider trading, they didn’t charge him with securities fraud. They turned to their Louisville Slugger instead.

Nathaniel Chastain, who allegedly bought and sold nonfungible tokens (NFTs) on the OpenSea app with secret information, was charged in June with wire fraud. The statute, along with the related mail fraud statute, is broad, adaptable and powerful. They’re federal prosecutors’ “Stradivarius, our Colt 45, our Louisville Slugger, our Cuisinart–and our true love,” federal judge and former prosecutor Jed Rakoff once quipped.

True love or not, wire fraud isn’t the typical approach in an “insider trading” case, which often involves securities fraud charges. But wire fraud can offer Justice Department prosecutors a key advantage in digital asset cases: the ability to dodge the knotty question of whether the asset is a security.

Chastain argued in court filings that an “‘insider trading’ wire fraud charge” requires “the existence of trading in securities or commodities.” Judge Jesse Furman in Manhattan rejected the argument last week and refused to dismiss the indictment.

Furman’s ruling reaffirms the Justice Department’s approach. It also underscores the flexibility DOJ has in policing markets for digital assets like NFTs and crypto tokens, compared to regulators at the Securities and Exchange Commission. The SEC’s jurisdiction is limited to enforcing securities laws.

The DOJ, which has taken an increased focus on digital assets under the Biden administration, can crack down on conduct that might fall outside the SEC’s reach. The Chastain case will likely be a model for prosecutors in similar cases, attorneys say.

“The decision opens up the possibility for future digital asset ‘insider trading’ actions without actually having to address that heavily debated question of whether a digital asset is a security,” Eversheds Sutherland (US) LLP attorney Andrea Gordon said. “They don’t even have to go into that.”

Wire fraud is a broad statute, and prosecutors have deployed it in a number of high-profile cases. Elizabeth Holmes, the founder of failed blood startup Theranos, and Trevor Milton, founder of the electric trick maker Nikola, were each convicted of wire fraud.

Federal prosecutors also relied on the statute to charge New Jersey officials in the “Bridgegate” scandal that clogged traffic on the George Washington Bridge, and in cases tied to the Varsity Blues college admissions scandal.

Chastain’s case is “an ideal illustration of the breadth of the principles of mail and wire fraud,” Robert Anello, a partner at Morvillo Abramowitz Grand Iason & Anello PC, said.

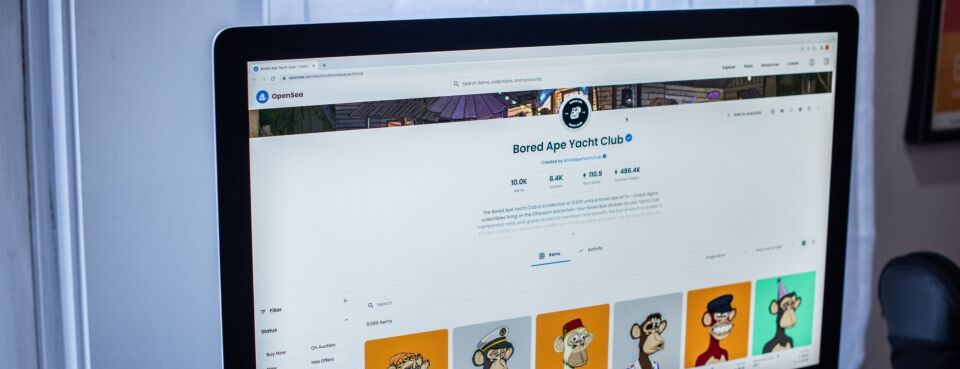

Chastain was responsible for selecting NFTs that were to be featured on OpenSea’s homepage, a placement that tended to raise the NFT’s value. Prosecutors allege he secretly bought dozens of NFTs shortly before they were featured, then sold them for a profit.

Announcing the charges in June, the DOJ called it the “first ever digital asset insider trading scheme.” He was also charged with money-laundering. The SEC has not brought a parallel action against Chastain.

Chastain says the NFTs he bought and sold aren’t a security or commodity. He argued that’s a prerequisite for insider trading charges. After all, the foundation of insider trading caselaw is the protection of financial markets, he said.

Furman, of the Southern District of New York, said in his order the argument was “wholly without merit.”

Chastain wasn’t charged with insider trading in the classic sense, which involves fraud under the securities laws, the judge said. Chastain was instead charged with wire fraud , under Section 1343.

“Section 1343 makes no reference to securities or commodities,” the judge said. “To accept Chastain’s argument would be to read an additional element into the wire fraud statute, which the Court may not do.”

Chastain’s lawyer, David Miller of Greenberg Traurig LLP, declined to comment.

The DOJ may have muddied the waters by touting the case as “insider trading,” but the legal theories in the indictment are sound, attorneys said.

“It’s straight-forward property fraud,” George Washington law school professor Randall Eliason said. “Calling it insider trading is just kind of a way to make a splash. But it’s really not, strictly speaking, insider trading.”

Prosecutors used the wire fraud approach in another digital asset-related case, against Ishan Wahi, a former product manager at the crypto exchange Coinbase. Wahi is accused of leaking secret information to help his brother and friend buy crypto tokens before they were listed on the exchange.

Wahi’s brother, Nikhil, pleaded guilty to a wire fraud charge last month.

Furman’s decision is clear that the DOJ can still pursue insider trading-like wrongdoings involving digital assets by using the wire fraud statutes when it’s not clear whether the assets are governed by the federal securities laws, said H. Gregory Baker, chair of the Securities Litigation group at Patterson Belknap Webb & Tyler LLP and a former SEC attorney.

This stands in contrast to the SEC.

The agency brought its own insider trading case against the Wahi brothers and the friend, Sameer Ramani. The SEC’s complaint alleges securities fraud, meaning the agency will have to prove relevant assets are securities.

To determine whether something is a security, regulators and courts use the so-called Howey Test, derived from a 1946 Supreme Court ruling. SEC chair Gary Gensler has said he thinks most digital coins are securities, although there remains a lot of ambiguity.

“It’s kind of the wild, wild west,” Gordon said.

Others argue that crypto acts more like a commodity, such as oil or grain. Coinbase, the crypto exchange platform, has insisted that it doesn’t list securities. The issue is also being raised in various lawsuits brought by investors. The DOJ, for now, can steer clear of that debate.

“If I’m the DOJ, I say let the CFTC, SEC, and the rest of the world fight out whether it’s a security, a commodity, or neither,” Anello said. “I don’t need to know that because I can prosecute people for any fraud.”

The SEC is in the midst of litigating a closely watched case that accuses Ripple Labs of misleading investors about its XRP crypto token. A central question in the case is whether XRP is a security, subject to SEC jurisdiction.

“If SEC gets bad decisions about whether cryptocurrencies are securities or not, they could really be hamstrung, whereas DOJ is going to have a much better tool to police fraud in this area,” said Ballard Spahr LLP attorney David Axelrod, a former federal prosecutor and SEC attorney.

Wire fraud has its own complications for prosecutors, as proving it requires that the defendant “deprive another of money or property.”

Furman said there was “some force” to Chastain’s argument that information about OpenSea’s homepage listings doesn’t constitute property.

Those questions—what is, or isn’t, property—can be tricky in their own right.

In the Bridgegate case, the US Supreme Court ruled the Port Authority’s interest in controlling the George Washington Bridge wasn’t an adequate property interest.

The US Court of Appeals for the First Circuit will hear arguments next month, related to the Varsity Blues investigation, that an offer of admission to a college isn’t property.

“If you had a case alleging someone took NFTs from their employer, that’s property,” Eliason said. “But if you’re arguing these internal business decisions about what we put on the website next week [are] property, that’s a lot dicier.”

To contact the reporter on this story: Matthew Bultman in New York at [email protected]

To contact the editor responsible for this story: Roger Yu at [email protected]; Maria Chutchian at [email protected]

To read more articles log in.

Learn more about a Bloomberg Law subscription