Menu

Search

About

Abigail Carlson is a web3 marketing manager at ConsenSys Mesh. She previously held communications roles on a political campaign, in higher education, and for non-profits and B corps. She's on Twitter @abi__carlson. (Disclosure: ConsenSys is one of 22 strategic investors in Decrypt.)

I had a realization recently while wandering through the Musée Matisse in Nice, France, where I went to see a temporary exhibit on David Hockney.

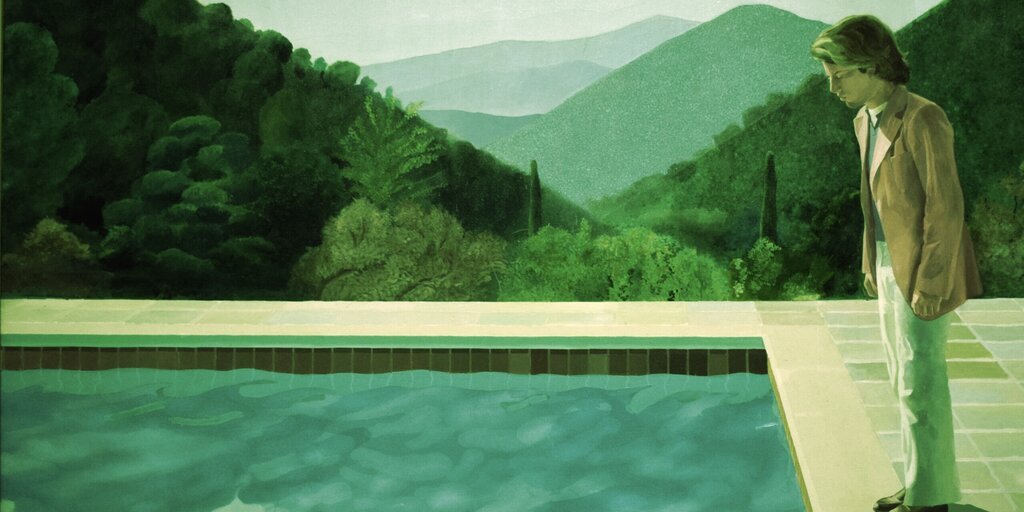

If you’re not familiar, Hockney is considered one of the most influential living modern British artists. His 1972 work "Portrait of an Artist (Pool with Two Figures)" sold at Christie’s auction house in 2018 and broke the auction house record at $90 million (a record broken the following year by Jeff Koons’ "Rabbit," which sold for $91 million).

What fascinated me at the Hockney exhibit wasn’t his paintings, even though I find them beautiful. What fascinated me most was the fact that he started experimenting with a new art form at age 67 by learning Photoshop with his sister Margaret. Where most artists at that age would have stuck with what they had known best, Hockney’s curiosity propelled him to try something new. In 2008, at age 71, Hockney got his first iPhone. By the following year he had made over a thousand digital paintings using his thumbs, and he now is a prolific digital artist. The exhibition I attended in Nice, "A Paradise Found," featured a yet-unseen series of iPad flower paintings.

Wandering around the exhibit I was struck by the following realization: The exhibit made no mention of NFTs.

I’m so used to equating NFTs with digital art that I was almost shocked to not see a mention of NFTs. A missed opportunity for Hockney? Maybe, although it’s doubtful the artist needs the extra income from selling these images as non-fungible tokens. In fact, Hockney has publicly criticized NFTs, calling them "silly little things."

I’m actually glad Hockney hasn’t moved into this realm, and thankful for his staunch perspective. It serves as an important reminder: NFTs and digital art are not synonymous. In fact, it’s time we start separating NFTs from digital art.

While digital art can certainly be made into an NFT, NFTs are ultimately a much wider category than that which is restricted to art, and I believe that associating the two too closely does a disservice to each.

Digital art is simply the latest evolution of humans using tools at their disposal to make art. From drawing on cave walls, to using pen, paper and paint, to experimenting with technology to create new forms of art (an overly banal description of the evolution of art over time, my apologies), humans will always use the tools in front of them to make art. This is because the process of creating is ultimately a fundamental part of what it means to be human.

While NFT collections do feature digital art, I would argue that the emphasis of many NFT collections isn’t on the art itself, rather on the marketability of the art.

NFT collectors look at stats like floor price and the ratio of owner volume to supply volume to gather insights on circulation and potential resale value. Of course, artist credibility and previous success also go a long way. To be clear, none of these things are wrong and neither are they purely restricted to the digital art realm. But the point I’m making is that many NFT collections, as we think of them in common parlance, are as much art as they are finance.

The fact that I have more than one investment banker friend who spends their weekends trading JPEGs is a case in point. To them, it’s a middle finger to a financial system that requires them to fit into a certain (fairly square) way of operating. If they can make as much money flipping an NFT as they can working “for the man,” who can blame them?

From artist patrons to auction houses, the intermingling of the worlds of finance and art is nothing new, and is in many ways a relationship that is necessary. But the arrival of NFTs has also brought an inordinate amount of rug pulls and scams that have plagued the space, leaving it to have to fight for its credibility. It’s no wonder that some digital artists may intentionally be steering clear of space out of fear their reputation could be sullied.

Digital art doesn’t have to be made into an NFT, and doing so may actually detract from the art itself (I will get to exceptions to this at the end). Meanwhile, there are a host of alternate use-cases for NFTs that are fascinating and will no doubt change much of how we operate. Here are a few of them:

Ticketing:

The ticketing industry we know of today has been plagued by a myriad of challenges from counterfeiting and fraud to a lack of exchange protocols. Issuing event tickets as NFTs allows for easy distribution and instant verifiability. There is also the possibility for ongoing royalties from sales on secondary markets which could go straight to stakeholders, artists and event organizers. This piece on NFT ticketing by BanklessDAO breaks the concept down nicely for the curious.

Music:

Before online streaming, most artists made money on the sale of physical music sales (97% of revenue back in 2001). While expanding access and the possibility of discovery for artists, streaming also destroyed music’s scarcity. NFTs bring some of this back through digital scarcity. Kings of Leon was the first band to release an album as an NFT (When You See Yourself) and made $2MIL off the sales.

Real estate:

NFTs have several use cases in real estate. For one, they can represent a physical property being purchased. While much of this will be contingent on legal prerequisites being met in an evolving industry, the technology is already being primed to make this a reality, and with reason. By buying an apartment with NFT asset properties, you would have immediate access to the entire history of the apartment, from previous buyers and investments to legal disputes and payments. You could also buy and sell property much faster than is currently the case given NFTs transfers happen immediately.

Another use case in real estate is tokenizing properties for shared investment via fractional ownership. In our current system, co-owning a property requires an inordinate amount of paperwork, time and legal fees. Fractionalizing real estate and selling tokens enables investors to easily be able to enter and exit an investment, and rules can be codified via smart contracts to determine how many weeks a year investors would have access to the property. In this way, co-ownership is actually tangible, as compared to investing in real estate through the likes of REITs. (To dig more into the interplay between NFTs and real estate, this is a good place to start.)

Sports:

Not an arena (pun intended) I know much about admittedly, but nonetheless one that is primed for huge acceleration of NFT adoption. Not only will ticketing be a use-case (see above), but sports clubs are increasingly moving into digital collectibles as a way to both increase fan engagement and earn additional revenue. An example of this is NBA Top Shot, officially licensed NBA digital collectibles. Owning NFTs can also be used as a gateway to IRL community events, by providing holders with opportunities to attend meet-and-greets with players. (For more, see here.)

Brands:

From fashion to luxury cars and goods, brands across the spectrum are experimenting with NFT collections. This could look like releasing an NFT alongside the purchase of a physical asset. RTFKT Studios pioneered this in 2021 when they released NFTs in tandem with physical sneakers — the campaign generated $31.MIL of revenue in 7 minutes. Dolce & Gabbana combined the physical and virtual in a collection in 2021 and made $5.65MIL.

For fashion brands in particular, NFTs can also be used as QR codes for supply chains. The entire supply chain for an item of clothing can be recorded on the blockchain, and scannable QR codes released as NFTs would allow consumers to check provenance on items of clothing they are interested in buying. This increased transparency could revolutionize not just fashion brands, but supply chains at large.

I’m not even going to get into the metaverse and gaming, but my point is that NFTs offer a wide array of applications beyond that of digital art, and my prediction is that we will soon start associating NFTs with a form of technology (they are ‘non-fungible tokens’, after all) instead of primarily with art.

To bring this full circle and because I can’t not play devil’s advocate, I still do think that digital art can be a fantastic use case for NFTs… in some instances.

One of these is generative art. Generative art is a subset of digital art that uses algorithmic codes to create an output, in a sort of unique ‘machine and artist’ type collaboration. Programming these codes requires skill and intentionality. Some collections or platforms require that a particular function be embedded in the code to curate the outcome for a certain aesthetic… In other words, the process itself is art.

Generative art is a perfect use-case for NFTs. Because the attributes of the artwork are randomly generated during the minting process, the person minting the artwork is brought into the creation process of the art itself — this can create a unique emotional bond with the piece of art.

One of the earliest examples of generative NFT art was the Chaos Machine, a project born in 2018 at the Distributed Gallery. The machine burns banknotes, and each time this happens music plays while a token is minted and QR code printed for the user.

Modern successful generative NFT collections often involve a set amount of mintable art pieces, strong communities, and a roadmap for the future. Generative collections that have revolutionized the digital art NFT space include Cryptopunks, Autoglyphs, BAYC, Chromie Squiggles, and Euler Beats in the generative music art space (Euler was initially incubated within MESH who I incidentally work for, but I promise I’m not biased).

Love them or hate them, the impact these giants have had on the NFT space cannot be denied, nor can it be denied that NFTs have provided them with a unique pathway to growing a revenue stream for their art as well as the ability to foster supportive communities.

Which takes me to the second reason NFTs can be a great use case for digital art: community. A lot of the prominent NFT collections mentioned above have resulted in interesting social experiments in the form of creating new communities. While it could be argued that this is art being used for an end versus art for art’s sake, there is something undeniably powerful about bringing people together around a common thread (pun intended again).

And note here: everyday artists who don’t primarily operate in the digital space can still issue NFTs, even if this is simply as a gateway into an online community. Painters, filmmakers, writers, musicians, etc, could release NFT collections that guarantee their fans access to a certain amount of events every year, meet-and-greets, and the like. Digital art NFTs can play a huge role in fostering community by token-gating its access, thus curating the community in a way beyond what is currently possible via social media and fan sites.

While I ultimately think NFTs should be dissociated from digital art, this is primarily because there are a myriad of use cases the technology can be used for, as well as because of some of the negative associations the space has unfortunately gathered. Digital art will always remain as one of those use cases, as it should.

One thing is sure, David Hockney will be fine either way. In the unlikely event he changes his mind about NFTs, I have no doubt that more than one NFT studio would be beyond happy to help transform his series of iPad flower paintings into a generative NFT art collection. But that just might be taking it a step too far…